WALLPAPER at Bank Street Arts

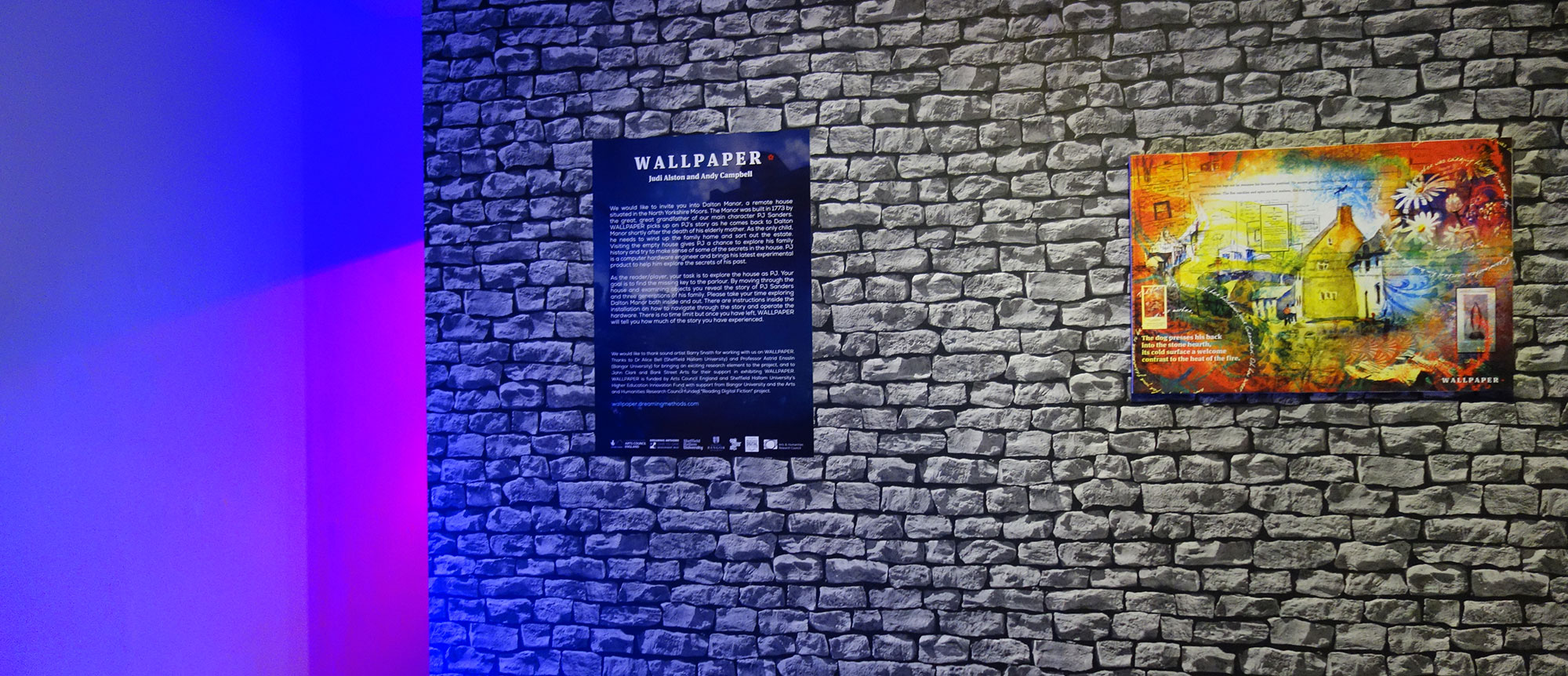

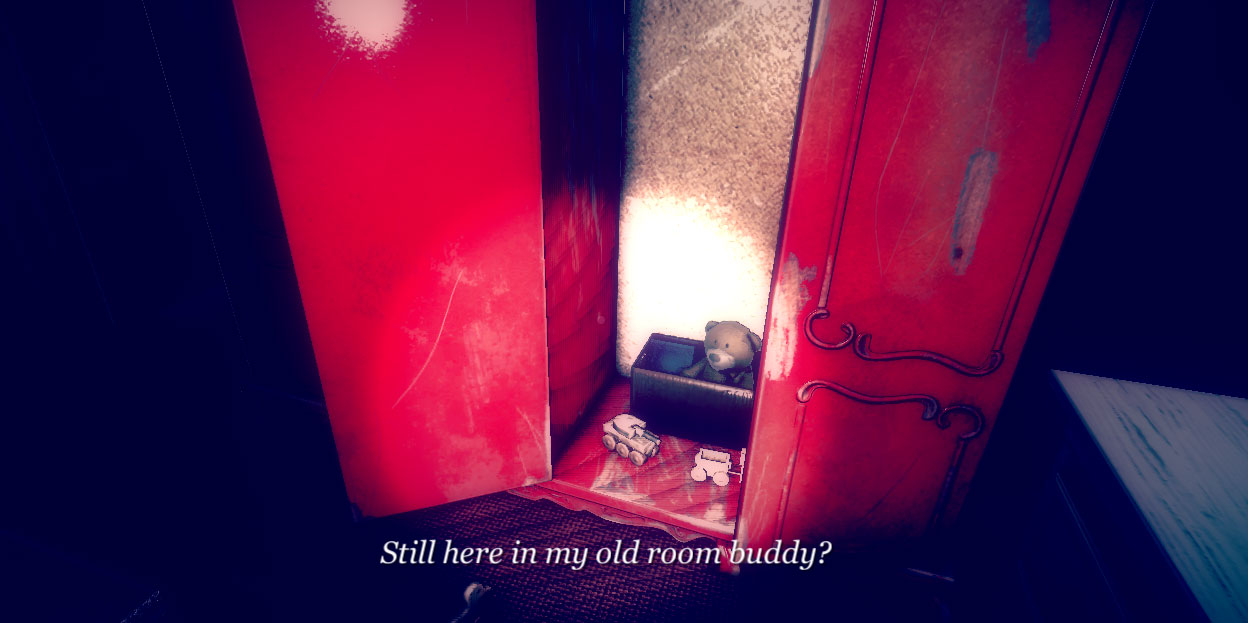

A few days before the launch of WALLPAPER at Bank Street Arts in Sheffield, final preparations were being made. The gallery space was transformed with a site specific installation made out of a wood frame structure, its temporary walls covered in a subtly textured Yorkshire stone imitation wallpaper. The space inside provided a highly focused, cinema-style environment for the games console and projection, alongside a seating area for up to six people. Speakers were installed and hidden; the insides were layered with drapes of blackout fabric; and outside lighting around the installation put in place to echo the colours of the digital work.

Our exhibition of canvases, inspired by and taken from the project itself, were hung, and iPads were installed to collect research around the impact of WALLPAPER on readers and audiences.

As opening time approached, there were last minute nerves, final checks and then ready to go. The door opened onto a wet, rainy and very blustery night. Surely no one would venture out on a night like this? Fears subsided as a continuous stream of people filled Bank Street Arts, a mix of ages and interests, but all here to explore our project.

“Tremendous experience – love the atmosphere of the visuals, storytelling and sound.”

It was humbling to have an audience of around 70 people gather to celebrate the launch of WALLPAPER. Bank Street Arts were amazing hosts and the venue was perfect for the occasion. Dr Alice Bell, our partner on WALLPAPER from Sheffield Hallam University, opened the event and put into context the research project surrounding it.

Andy and I both spoke about different parts of the project and thanked our collaborator sound artist Barry Snaith for his work. The atmosphere was vibrant and exciting. Our audience wanted to explore and understand what WALLPAPER is and how digital narratives can be accessed and enjoyed. The feedback from the launch night was exceptional. We asked people to comment on social media via #WALLPAPERstory which also provided useful content towards our evaluation.

“Very well done. Lovely atmosphere, brilliant attention to detail.”

The following week we returned to Sheffield to do an ‘artists talk’. It was a small gathering of about 12 people who were all incredibly interested in the subject, ranging from how we used technology, through to the story line and the many ways we’d used different digital media. We gave a potted history of our work in this field and organisation, gave a glimpse of some of our other current projects and offered an insight into how WALLPAPER was created, especially the writing and development process and how the two became intricately fused. It was a good session and a very positive place to nurture potential links for future collaboration.

“Held my breath through most of it… Beautiful design and incredibly immersive.”

Our academic partners Dr Alice Bell (SHU) and Professor Astrid Ennslin from Bangor University headed up ‘Reader Group’ sessions around the WALLAPER exhibition. WALLPAPER remained at Bank Street Arts for just under a month and was open to the public most days. There was a steady flow of visitors and we have accumulated some really interesting and informative feedback.

“Intuitive and naturally intriguing, great that you aren’t just sat consuming the story but actually uncovering it.”

Our thanks go out to Bank Street Arts and their team for great support, and to all the visitors who took time to come in and explore the work, often leaving really well thought-through positive feedback.

Next stop with WALLPAPER in 2016 is the Ponteo Centre at Bangor University where we’ll be adapting the work to suit this (very different) space. Bring it on… 🙂